What Does a Baby Crane Look Like? Everything You Need to Know

Have you ever wondered what a baby crane looks like? These elegant birds start life looking nothing like the tall, regal adults we often see wading through wetlands. Baby cranes—also known as crane chicks—are fuzzy, awkward, and surprisingly adorable.

In this guide, we’ll walk you through everything you need to know about a baby crane’s appearance—from their size and coloration at hatching, to how they gradually transform into the majestic long-legged birds that capture our imagination. Whether you’re a birdwatcher, a wildlife lover, or just plain curious, you’ll find this glimpse into a baby crane’s early life both fascinating and heartwarming.

Physical Characteristics of a Baby Crane

When cranes hatch, they’re precocial, meaning they’re relatively mature and mobile. Baby cranes exhibit some defining features:

Appearance at Birth

- Downy Feathers: Baby cranes are born covered in soft, fluffy down feathers, typically tan, brown, or cinnamon-colored. This camouflage helps them blend into their marshy or grassy surroundings.

- Size and Weight: At birth, crane chicks weigh around 90-150 grams (approximately 3-5 ounces) and stand about 6 inches tall.

- Legs and Feet: Even at a young age, cranes have disproportionately long legs, perfect for navigating through tall grasses and shallow wetlands.

Developmental Changes

As they grow, young cranes experience significant changes:

- Feather Coloration: Juvenile cranes gradually lose their downy feathers, replacing them with mottled gray and brown plumage. Juvenile Sandhill cranes typically develop reddish-brown feathers on their backs.

- Size Growth: Young cranes rapidly increase in size, reaching nearly adult height within 3-4 months, although full adult weight takes up to a year.

According to the Cornell Lab of Ornithology, juvenile Sandhill cranes can be distinguished from adults by their lack of red crowns and overall duller plumage (source: Cornell Lab of Ornithology).

Behavior and Diet of Young Cranes

Feeding Habits

Baby cranes initially rely on their parents for food. Crane parents feed their young insects, worms, and small amphibians. Within a few weeks, juveniles start foraging independently, consuming seeds, berries, grains, and small animals.

Learning to Forage

Young cranes closely mimic their parents’ behaviors, learning essential survival skills such as identifying edible plants and catching prey.

Habitat and Nesting

Cranes typically choose to nest in secluded, wetland environments, such as marshes, bogs, shallow lakes, and grassy riverbanks. These habitats provide the ideal combination of water, dense vegetation, and isolation, which are crucial for successfully raising their young.

A typical crane nest is a shallow mound made of reeds, grasses, and other wetland plants, often built directly in shallow water or on a small island. This placement helps deter ground predators and gives the parents a clear view of any approaching threats.

Once hatched, baby cranes—called chicks or colts—remain close to the nest for the first several days, staying hidden in thick vegetation. This camouflage, combined with the quiet behavior of the chicks, protects them from common predators like:

- Foxes and raccoons

- Coyotes and feral dogs

- Large raptors, including hawks, eagles, and owls

During this vulnerable stage, both crane parents take turns vigilantly guarding the nest and guiding the chicks toward safe feeding grounds nearby. While baby cranes are precocial (born with their eyes open and able to walk), they rely heavily on their parents for warmth, food, and protection.

This early period in a chick’s life is critical—not just for survival, but for learning essential behaviors like foraging, vocalizing, and responding to danger. A well-hidden, resource-rich nesting site can make all the difference in whether a baby crane makes it to adulthood.

Vocalizations and Crane Sound

Young cranes produce distinct vocalizations that differ from adults:

- Soft Peeping Sounds: Newly hatched cranes make gentle peeping noises to communicate with parents.

- Begging Calls: As juveniles grow, they produce louder, more persistent sounds when hungry or distressed.

Adult cranes, in contrast, make louder, trumpet-like calls. Young cranes gradually develop their full vocal capabilities over several months.

Whooping Crane Sound:

Baby Sandhill Cranes:

Life Cycle and Migration Patterns

Juvenile Sandhill cranes start practicing flight around 70-80 days after hatching. Initial flights are short, but they soon become proficient flyers capable of joining their parents on migration routes.

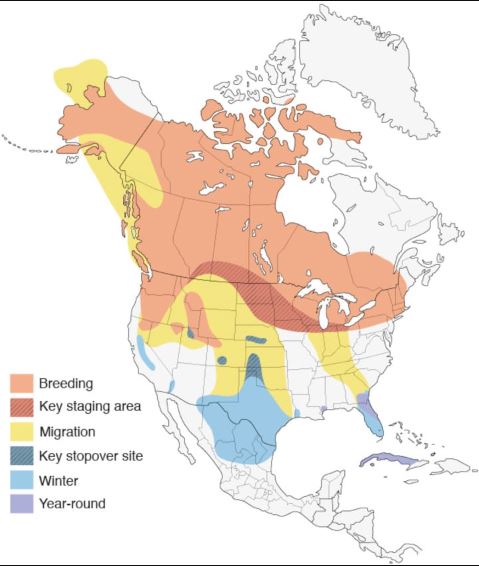

Migration Habits

Sandhill cranes typically migrate in family groups. Juvenile cranes learn migration routes from their parents, ensuring successful navigation across vast distances.

According to the International Crane Foundation, these migrations can cover thousands of miles, with young cranes traveling to wintering grounds in warmer climates alongside adults (source: International Crane Foundation).

Conservation and Protection of Baby Cranes

Threats to Juvenile Cranes

Young cranes face multiple threats:

- Habitat Loss: Development and agriculture diminish natural crane habitats.

- Predation: Juvenile cranes are particularly vulnerable to predators due to their small size and limited mobility initially.

- Human Disturbances: Noise and environmental pollution disrupt crane nesting and feeding behaviors.

Conservation Efforts

Cranes are among the most iconic and endangered bird species in the world, making conservation efforts not just important—but urgent. With threats ranging from habitat loss to climate change and human disturbance, protecting these majestic birds requires a global, collaborative approach.

One of the primary challenges cranes face is the destruction of wetlands, which are essential for nesting, feeding, and migration. As agricultural expansion, urban development, and industrial drainage continue to shrink these habitats, many crane populations are in steady decline.

To combat this, numerous conservation organizations have stepped in with focused, long-term strategies:

International Crane Foundation (ICF)

Based in Wisconsin, the ICF is a global leader in crane conservation. They operate in over 50 countries, working to:

- Protect and restore critical crane habitats

- Monitor wild crane populations

- Collaborate with local communities to develop sustainable land-use practices

- Conduct captive breeding and reintroduction programs for critically endangered species like the Whooping Crane and Siberian Crane

Audubon Society

The Audubon Society promotes wetland conservation across North America through:

- Policy advocacy for stronger environmental protection laws

- On-the-ground habitat restoration projects

- Public education campaigns that raise awareness of crane conservation

- Support for Important Bird Areas (IBAs), many of which are vital crane habitats

Community and International Involvement

In regions like Africa and Asia—home to vulnerable species such as the Blue Crane and Red-crowned Crane—grassroots efforts have proven effective. Local farmers are taught how to farm more sustainably in crane-rich areas, and ecotourism projects provide financial incentives for protecting nesting grounds.

Global Collaboration

Organizations like the Convention on Migratory Species (CMS) and BirdLife International also play a key role in cross-border conservation initiatives, especially since many crane species migrate thousands of miles each year across continents.

Thanks to these combined efforts, some species—like the Whooping Crane—have made remarkable recoveries, though they are still far from safe. Ongoing research, public support, and sustained funding are essential to ensure that cranes continue to dance across the world’s wetlands for generations to come.

How to Help Juvenile Cranes

Juvenile cranes—also known as colts—are particularly vulnerable during their early months of life. While they are precocial and can walk shortly after hatching, they still rely heavily on their parents for protection and guidance. Their survival depends not only on nature but also on how humans interact with their environment.

If you live near or visit crane habitats, here’s how you can help:

1. Keep a Respectful Distance

Getting too close to crane families can cause stress or even nest abandonment. The International Crane Foundation (ICF) emphasizes:

“Disturbance during the breeding season can cause cranes to abandon their nests, eggs, or even young chicks.”

(Source – International Crane Foundation)

To avoid this:

- Observe cranes from a distance using binoculars.

- Stay on designated trails during breeding season (spring to early summer).

- Never feed or approach baby cranes, even if they seem alone.

2. Avoid Disturbing Wetlands

Cranes nest in quiet, marshy areas with dense cover. These habitats are increasingly threatened by human encroachment. According to Audubon,

“Wetlands are among the most productive and important ecosystems on Earth—and among the most endangered.”

(Source – Audubon Society)

To help:

- Avoid wetland areas during nesting season.

- Keep pets on a leash, especially near nature reserves.

- Don’t fly drones or create noise disturbances near waterfowl areas.

3. Support Conservation Programs

Whether globally or in your own backyard, your support matters. The International Crane Foundation runs effective programs that:

- Monitor and protect wild crane populations

- Restore wetlands

- Educate communities on crane-safe land use practices

You can:

- Donate or volunteer at savingcranes.org

- Support local eco-friendly farming initiatives

- Adopt a crane through symbolic donation programs

4. Spread Awareness

Raising awareness creates ripple effects. Encourage others to care about cranes by:

- Sharing credible articles or videos

- Talking to schools or local nature centers

- Supporting art or writing projects about crane conservation

Every small action contributes to a larger movement. As the ICF puts it:

“When we protect cranes and the wild places they depend on, we also safeguard our own future.”

(International Crane Foundation)

FAQs about Baby Cranes

How long do baby cranes stay with their parents?

Young cranes stay with their parents for around 9-10 months, often through their first migration cycle.

What do juvenile Sandhill cranes eat?

Juvenile Sandhill cranes eat insects, seeds, grains, small amphibians, and occasionally small rodents.

Can juvenile cranes fly immediately after hatching?

No, juvenile cranes typically begin flying around 2.5-3 months old.

What predators threaten young cranes?

Common predators include foxes, raccoons, coyotes, large birds of prey, and occasionally snakes.

Why are crane chicks called “colts”?

Crane chicks are called “colts” because of their long legs and awkward, colt-like gait in their early development stages.

Conclusion

Understanding the life and development of baby cranes, particularly juvenile Sandhill cranes, enriches our appreciation of these remarkable birds. With proper conservation and awareness, we can ensure these beautiful creatures continue to thrive and captivate future generations.