Can Ducks Fly? Exploring Wing Structure, Muscle Power, and Migration

As someone who has spent over a decade observing birds in both tranquil wetlands and frigid flyways, one question I often hear from curious minds is: “Can ducks really fly?” The confusion is understandable. We typically see ducks waddling around ponds, dipping underwater, or flapping in short bursts across lakes. They seem like water specialists, not aerial acrobats.

But here’s the scientific truth: Yes, ducks can fly—and many of them are exceptional fliers. In fact, several duck species undertake some of the longest and most physically demanding migrations in the avian world.

In this article, I’ll dive into the wing anatomy, muscle structure, and flight behavior of ducks. We’ll explore how evolutionary biology has shaped their ability to fly, examine the differences between dabbling and diving ducks, and uncover the vital role flight plays in their seasonal migrations. Throughout the guide, I’ll include findings from authoritative studies and ornithological research where relevant to provide accurate, evidence-based insights.

Can Ducks Fly? Yes—But Not All the Same Way

The short answer is yes, ducks can fly. But not all ducks fly with the same efficiency, altitude, or purpose. Some species, like the Mallard (Anas platyrhynchos), are strong fliers capable of migrating hundreds or even thousands of miles. Others, such as domesticated breeds, may have lost much of their flight ability due to selective breeding.

What often misleads people is how ducks transition between water and air. Their takeoff style is quite different from songbirds. Most ducks need a running start across the water before becoming airborne. This technique, while not the most elegant, is incredibly effective when paired with their powerful flight muscles and wing dynamics.

Wing Structure: Built for Powerful, Fast Flight

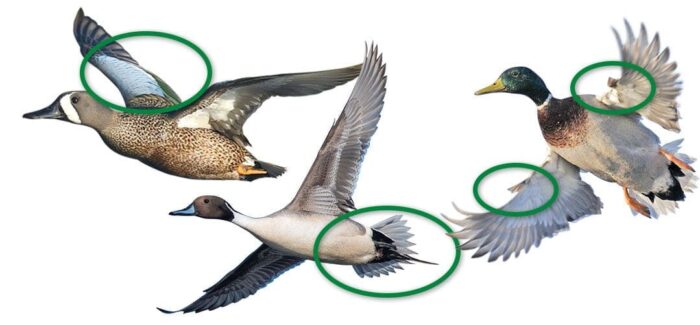

When studying birds, wing shape offers essential clues about flight style. Ducks typically have pointed, narrow wings with a relatively high aspect ratio. This design is ideal for fast, sustained flight, especially over long distances.

Key Features of Duck Wings:

- Wing Loading: Ducks have high wing loading (body mass relative to wing area), meaning they need to fly faster to stay aloft. This is why ducks often appear to fly in a straight, rapid line.

- Pointed Tips: These help reduce air resistance and allow better energy efficiency during migration.

- Strong Primary Feathers: The outer flight feathers are rigid and powerful, aiding both lift and thrust.

According to research published in The Auk: Ornithological Advances, migratory ducks like the Northern Pintail (Anas acuta) can fly at speeds exceeding 40 to 60 miles per hour, depending on tailwinds and weather conditions.

Muscle Power: The Engine Behind Duck Flight

Flight is one of the most energy-intensive activities in the animal kingdom. Ducks are equipped with powerful pectoralis muscles, which control wing flapping, and make up about 15–25% of a duck’s total body mass—a remarkable adaptation.

Highlights of Duck Muscle Anatomy:

- Pectoralis Major: Main muscle responsible for the downstroke, which generates lift.

- Supracoracoideus: Assists in the upstroke, particularly crucial for takeoff.

- Aerobic Muscle Fibers: Ducks, especially migratory ones, have a high concentration of red muscle fibers packed with mitochondria, allowing sustained energy output over long periods.

According to the Cornell Lab of Ornithology, these muscular adaptations are what enable ducks like the Blue-winged Teal to travel up to 7,000 miles during migration without complete exhaustion.

Dabbling vs. Diving Ducks: Flight Style Differences

To understand duck flight better, it’s helpful to distinguish between two major groups:

1. Dabbling Ducks (e.g., Mallards, Northern Shovelers)

- Flight Style: Agile and quick, they launch directly from the water.

- Wingbeats: Fast and shallow.

- Migration: Typically cover medium to long distances.

- Behavior: Feed near the surface and rarely dive deep.

2. Diving Ducks (e.g., Canvasbacks, Redheads)

- Flight Style: Heavier and more labored takeoff; often require a running start.

- Wingbeats: More rapid and deeper.

- Migration: Some species, like the Greater Scaup, are long-distance migrants.

- Behavior: Dive deep for food; more compact body for underwater agility.

Diving ducks are generally less maneuverable in flight but compensate with stronger wingbeats and endurance.

Migration: Ducks as Long-Distance Fliers

Ducks are among the most remarkable migrators in the bird world. Many North American species breed in the Arctic or northern U.S. and winter in Central or South America. These journeys are not casual flaps over a few ponds—they are feats of endurance and navigation.

Examples of Migratory Flights:

- Northern Pintail: Travels up to 6,000–7,000 miles between North America and Central America.

- Blue-winged Teal: One of the longest duck migrations, often flying from Canada to South America.

- Mallard: Highly adaptable, found flying from Alaska to the Gulf Coast.

Ducks often use flyways, which are migratory highways in the sky. North America has four major flyways:

- Atlantic Flyway

- Mississippi Flyway

- Central Flyway

- Pacific Flyway

Each of these routes is shaped by geography and food availability, with wetlands, lakes, and rivers serving as key rest stops.

Flight Altitude and Speed

You might be surprised at how high ducks can fly. According to data collected using radar and banding studies:

- .Most ducks fly at altitudes between 200 and 4,000 feet.

- During migration, some species have been recorded at over 20,000 feet, especially when crossing mountainous terrain like the Rockies.

In terms of speed:

- Mallards: ~55 mph

- Canvasbacks: ~60 mph

- Blue-winged Teals: ~50 mph

Pair this with wind assistance, and ducks can cover hundreds of miles in a single night of flying.

Can All Ducks Fly?

While most wild ducks are excellent fliers, there are a few exceptions:

Flightless Ducks:

- Steamer Ducks (Tachyeres spp.):

- Native to South America.

- Some species are completely flightless.

- Adapted for life on the water with strong legs and dense bodies.

- Domesticated Ducks (e.g., Pekin, Rouen):

- Bred for meat or eggs.

- Heavier body mass and smaller wings make flight nearly impossible.

- Occasionally capable of short “hops” but not sustained flight.

These exceptions are typically due to evolutionary adaptation or artificial selection—both leading to reduced flight capacity.

Flight and Survival: Why Flying Matters for Ducks

Flight is essential to a duck’s survival strategy. It enables:

- Escape from predators (foxes, hawks, humans)

- Access to feeding and breeding grounds

- Climate and seasonal adaptation

- Dispersal of populations to prevent overcrowding

Without flight, ducks would be severely limited in range and ecological success. Their migratory habits also aid biodiversity, as they carry plant seeds, aquatic life, and even insect larvae across vast distances.

Fun Fact: Ducks in Space?

Well—not quite space, but a Northern Pintail once banded in Alaska was later recovered in Japan, showing a trans-Pacific flight path. This means that certain ducks can cross oceans using favorable wind patterns, a feat comparable to any jetliner.

Conservation Note

Migration exposes ducks to many threats, including:

- Habitat loss (especially wetlands)

- Hunting pressure

- Climate change affecting migratory timing

- Pollution and lead poisoning

Organizations like Ducks Unlimited, the Audubon Society, and the Cornell Lab of Ornithology are actively working on conservation solutions, such as wetland restoration and migratory bird tracking.

Final Thoughts from the Field

After 13 years in the field, watching flocks of Northern Shovelers sweep across the horizon or witnessing a solitary Bufflehead launch like a torpedo, I’m continually amazed at what ducks are capable of. Their flight isn’t just functional—it’s an essential part of their identity as a species.

So, the next time you see a duck cruising across the sky in perfect V-formation, know this: you’re not just watching a bird in flight—you’re witnessing a finely-tuned biological marvel.

FAQs

1. Can all ducks fly?

Most wild ducks can fly, but some domesticated breeds and a few wild species, like certain steamer ducks, are flightless due to body structure or selective breeding.

2. How far can ducks fly during migration?

Some ducks, such as the Blue-winged Teal, can fly over 7,000 miles during migration. Many species cover hundreds to thousands of miles seasonally.

3. Why do some ducks struggle to take off?

Ducks have high wing loading, meaning they need more speed to become airborne. Many require a running start across water to generate lift.

4. Do ducks fly at night or during the day?

Many duck species migrate at night, using stars and Earth’s magnetic field to navigate, while others may fly during the day depending on conditions.

5. What’s the difference in flight between dabbling and diving ducks?

Dabbling ducks take off quickly and fly more agilely, while diving ducks are heavier, need a longer running start, and have stronger wingbeats for sustained flight.