Baby Turkey 101: What They’re Called, What They Eat, and How to Help Them Thrive

By Rifat Ahmed, Birdwatching Enthusiast with 13+ Years of Field Experience

Over the past 13 years of birdwatching, few moments have captured my attention quite like seeing a brood of baby turkeys scurry through tall grass under the watchful eye of their mother. These little birds are not only adorable, but they also offer fascinating insight into the wild turkey’s complex and communal life cycle.

In this comprehensive guide, I’ll answer the most common questions about baby turkeys—what they’re called, what they eat, how they survive in the wild, and how to care for them in captivity. Whether you’re a bird lover, a backyard wildlife observer, or someone raising heritage turkeys, this guide will give you expert-level knowledge grounded in science and firsthand experience.

What Is a Baby Turkey Called?

Let’s begin with the basics. A baby turkey is called a “poult.”

The term “poult” applies to young turkeys—both male and female—up to about 4 to 5 weeks old. After this stage, they’re typically referred to as juvenile turkeys until maturity.

Here’s a quick breakdown of turkey life stages:

- Egg – Incubation lasts about 28 days.

- Poult (0–4 weeks) – Fully dependent on the hen.

- Juvenile (4 weeks–4 months) – Begins roosting and foraging more independently.

- Adult (4+ months) – Reaches sexual maturity at around 7 to 10 months.

In the field, I’ve often observed that poults stick tightly to their mother’s side for the first few weeks, forming what we call a brood. The mother turkey, or hen, is fiercely protective during this stage.

How Baby Turkeys Are Born

Wild turkeys begin nesting in early spring. According to All About Birds, females lay 10 to 14 eggs in shallow, hidden ground nests often surrounded by brush or grass.

Once the eggs hatch:

- Poults are precocial, meaning they are born fully feathered and with open eyes.

- Within 24 hours, they leave the nest and start following the mother.

- Unlike many songbirds, baby turkeys can walk, run, and peck at food almost immediately.

From my field notes in early May near the Appalachian foothills, I’ve seen hens leading lines of poults as they move from the nest site to feeding grounds—always alert, always scanning for predators.

What Do Baby Turkey Eat?

In the Wild

One of the most common questions I get is: what do baby turkey eat in the wild? The answer is: a protein-rich, omnivorous diet.

For the first few weeks, poults rely heavily on:

- Insects (ants, grasshoppers, beetles)

- Spiders

- Small invertebrates

- Tender greens and seeds

High protein is crucial for their rapid growth and feather development. A study from the University of Georgia found that poults consume more than 70% insects in the first two weeks.

By the time they’re 4–6 weeks old, they begin shifting to:

- Berries (blackberries, wild grapes)

- Grass seeds

- Acorns (in crushed form)

- Small grains

In Captivity

If you’re raising poults at home or on a farm:

- Starter feed (28% protein) is recommended for the first 6–8 weeks.

- Supplement with finely chopped boiled eggs, mealworms, or crickets.

- Avoid large grains like corn early on—they can be a choking hazard.

Don’t forget access to clean, fresh water at all times. Shallow dishes prevent drowning risks for tiny poults.

How Baby Turkeys Survive in the Wild

Survival is tough for baby turkeys. In fact, fewer than 50% of poults survive past their first month in the wild. Here’s what helps improve their chances:

1. Camouflage

Poults have brownish, mottled down that blends seamlessly with the forest floor. When danger approaches, they flatten themselves and freeze—an instinct I’ve seen save countless poults from predators like foxes or hawks.

2. Brood Cohesion

Hens keep their poults together. A scattered brood is a vulnerable brood. I once observed a hen spend nearly an hour retrieving a lone poult that had strayed too far into a meadow.

3. Roosting Habits

By 2–3 weeks of age, poults begin roosting in low branches at night—far safer than staying on the ground. This is a major milestone in their development.

How to Identify Baby Turkeys

Even seasoned birdwatchers—myself included—have occasionally mistaken baby turkeys (poults) for other young ground birds like quail or pheasant chicks, especially at a distance. That’s because many precocial birds share similar features early on: small bodies, speckled down, and ground-dwelling behaviors. However, once you know what to look for, baby turkeys are quite distinct.

Key Physical Features of a Poult

- Coloration: Baby turkeys are typically light brown to tan in color, with buff or grayish speckling across their back, head, and wings. This pattern provides excellent camouflage against forest floors, leaf litter, and dry grasses. Unlike pheasant chicks—which often have richer golden tones—or quail chicks, which are darker and rounder, poults have a slightly duller, more muted appearance that blends well with their surroundings.

- Size: At hatch, poults weigh around 2.5 ounces, making them larger than quail chicks but slightly smaller than domestic chicken chicks. They also have longer necks and legs than most other ground birds, giving them a lankier silhouette.

- Beak Shape: The short, slightly curved beak of a poult is designed for pecking at insects and soft vegetation. It’s not as slender as a songbird’s beak or as blunt as a duckling’s bill—falling somewhere in between.

- Legs and Feet: One of the most defining characteristics is their long, muscular legs, even at just a few days old. This is no coincidence—poults are built for speed. Their strong legs help them keep up with the hen and escape predators. Their feet have three forward-facing toes and one backward, ideal for navigating brush and forest edges.

Behavioral Cues

- Group Dynamics: Poults almost always stay in tight formation with their brood and are rarely seen alone. If you spot a group of 8 to 12 small, speckled chicks following a single adult hen, there’s a very high chance they’re wild turkeys.

- Foraging Behavior: From day one, poults are constantly pecking at the ground, exploring for insects, seeds, and other morsels. Their feeding behavior is deliberate and focused, often mimicking the hen’s actions.

- Vocalizations: Listen closely. Poult calls are soft peeps and chirps, especially when separated or alerting their mother. These are different from the high-pitched “chee-chee” of quail or the squeaky calls of pheasant chicks.

How Poults Change Over Time

As poults grow, their appearance begins to shift noticeably:

- 2–3 Weeks: Wing feathers begin to emerge clearly, allowing short fluttering hops and low roosting.

- 4–5 Weeks: Body feathers start replacing down, especially on the chest and back.

- 6–8 Weeks: Males may begin to show early signs of a snood (the fleshy growth above the beak) and caruncles (small fleshy bumps on the neck and face), though these are subtle at first.

- 8–10 Weeks: Wing primaries are well developed, and poults can fly short distances or roost higher in trees. Plumage darkens to a more bronze-brown sheen, resembling adults.

These details have helped me accurately identify wild turkey poults across multiple habitats—from the hardwood forests of Pennsylvania to the open fields of Missouri. Once you’ve seen them in the wild, the unique combination of size, behavior, and body structure will stick with you for life.

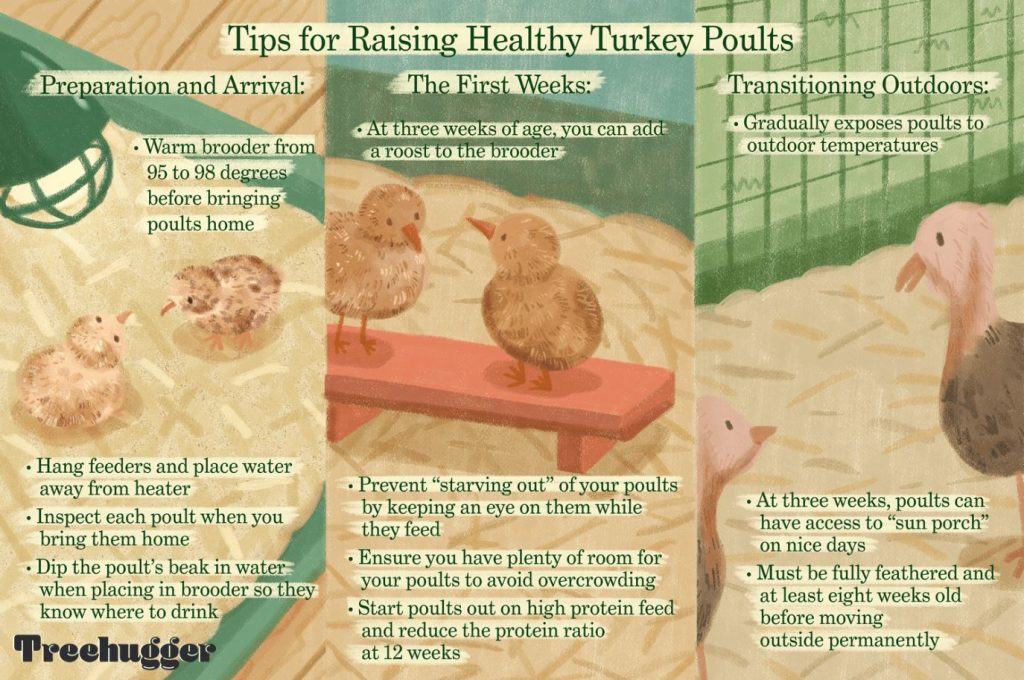

Raising Baby Turkeys at Home: A Care Guide

From backyard flocks to heritage turkey farms, more people are raising baby turkeys. Here’s my advice if you’re starting out:

1. Brooder Setup

- Temperature: Start at 95°F (35°C) for week one, dropping 5°F weekly.

- Bedding: Use pine shavings (avoid newspaper—it’s slippery).

- Space: Allow 1 square foot per poult initially.

2. Nutrition

- Starter feed (28% protein)

- Add hard-boiled egg yolks and finely chopped greens by week 2–3.

- Fresh water with marbles or stones to prevent drowning.

3. Health Monitoring

Watch for:

- Pasty butt: Dried feces block vent—clean gently with warm water.

- Leg splaying: Use non-slip surfaces and vitamin supplements.

- Respiratory issues: Ensure proper ventilation and dry bedding.

4. Socialization

Turkeys are highly social. Raise them in groups, and consider putting a mirror in their brooder to reduce stress if alone.

Differences Between Wild and Domestic Baby Turkeys

| Trait | Wild Poult | Domestic Poult |

|---|---|---|

| Diet | Insects, greens, seeds | Starter feed, supplements |

| Growth | Slower, more athletic | Faster, heavier |

| Survival Skills | Strong instincts | More dependent |

| Roosting | Begins at 2–3 weeks | Often not until older |

| Coloration | Mottled for camouflage | Varies by breed |

Domestic poults have been bred for size and meat production. Their wild cousins, however, are leaner, faster, and more adapted to avoiding predators.

When Do Baby Turkeys Become Adults?

- 4 Weeks: Fully feathered wings, beginning to fly short distances.

- 8 Weeks: Roosting higher, males start developing wattles and snoods.

- 16 Weeks: Referred to as young toms (males) or young hens (females).

- 7–10 Months: Full sexual maturity, may begin mating displays.

In the wild, toms often leave the family group by fall, forming bachelor flocks, while young hens may stay with their mothers into the winter season.

Fun Facts About Baby Turkeys

- They’re expert runners—poults can run up to 15 mph just days after hatching.

- They chirp, peep, and trill to communicate with their siblings and mother.

- One hen can raise poults from multiple nests—sometimes taking over abandoned broods.

- They imprint within 24 hours—often on the first moving object they see.

- They can fly short distances by 10–14 days, though not very high.

Final Thoughts from the Field

Every time I observe baby turkeys in the wild, I’m reminded of how delicate and determined life is. From their camouflaged feathers to their fearless dashes through brush, poults are miniature survivors. As birdwatchers, farmers, or backyard naturalists, it’s up to us to protect their habitats and give them the best start possible—whether that’s in a hardwood forest or a backyard brooder.

FAQs About Baby Turkeys

Q: What is a baby turkey called?

A: A baby turkey is called a poult until around 4–5 weeks of age.

Q: What do baby turkey eat in the wild?

A: Mostly insects, spiders, greens, and seeds for high protein and quick growth.

Q: Can baby turkeys fly?

A: Yes, they start flying short distances at around 10–14 days old.

Q: How do you take care of a baby turkey at home?

A: Provide a warm brooder, high-protein feed, clean water, and social interaction.

Q: When do baby turkeys leave their mother?

A: Around 4 to 5 months, though males may leave earlier to join bachelor flocks.